Across Scales:

The Work of Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Charles Renfro’s interest in architecture began when he was just around eight years old, when—not wanting to go to school because of being bullied—, he asked his mom to take him to look at buildings instead. His interest and admiration towards architecture continued and he ended up pursuing undergraduate degree and graduate degrees in architecture from Rice University and Columbia University, respectively. Since then, he has established his professional life in NYC.

In 1997, Renfro was introduced to Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, who had an interdisciplinary design and architecture practice. He was there to help out with a project—the Brasserie—but ended up with further collaborations while maintaining his private practice for the following years. And by 2004, Renfro became a partner of the firm, changing its name to Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R). As of present, the three continue to lead the firm along with a fourth partner, Benjamin Gilmartin. Although Renfro recognizes DS+R are working with large scale projects, he still considers the work culture in the office as a medium size firm; one where the creative aspect of the profession is highly valued.

An advocate of the LGBTQ+ community, Renfro credits his childhood and identity as part of his formation in architecture. In our conversation, he shares his thoughts on his creative process, office culture, how architects learn by ‘making’, innovation in projects, and an architect’s role in society regarding social issues and equality.

Hello Charles! How are you?

How are you? Nice to see you all!

Nice to see you too. It is an honor to have you here.

Right! “Be here”.

Right! Virtually!

I think that your home looks like my home office. You guys have those wonderful strange tropical backdrops.

These were created by Regner. I think he was going to send them on the chat. Not sure, but yes. It’s an ode to last year’s launch party, which had this really great beautiful green wall at the rooftop at a hotel, but since we’re not allowed to congregate, I ask a designer—Jaques Zekian—to do a 3d version of the foliage in glass and copper, so this is where we’re at.

Oh wow! That is Amazing.

This is our party tonight. Alright, so, to begin, by the age of 8 you knew you wanted to be an architect. You used to ask your mom to drive you around Texas to see buildings, and then later on, used a Kenner Girder & Panel Building Set, which is a toy, to create new and improved buildings. Do you still use this or other kinds of toys as a guilty pleasure, disguised as a conceptual design tool?

First off, that picture [shown on the screen] was from a year ago, and after I saw that picture, I went to get Botox, just to let you know—there is vanity to the family. And second, yes, that Girder & Panel set has been with me from my childhood. I pull it out and made different things over the years in my old block in Brooklyn. Here in my house in Chelsea, Manhattan, it was really inspiration when I didn’t have a practice, when I was a child, and I would recreate buildings that I saw on the cover of Architectural Record.

I had to have been the youngest person to get a subscription to Architectural Record. I did that in junior high, they wouldn’t even let me do it because I was not a professional, so I had to have my dad do it. But I would see images of buildings on the cover and I would make them out of this Girder & Panel Set, and the most elaborate one I remember making was I.M. Pei’s Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, here in New York. I literally fashioned my own mirror panels out of tin foil, I cut them precisely the same size, and I made the exact stepping pyramidal structure that defines the convention center now. So, now that I practice more, I would say I use it less, because I’m actually making the stuff, blown up.

Alright! I read that you added a lounge to soften the office’s workaholic culture, which is something really instilled on designers form early on their education. It seems like a taboo to ask about work-life balance in big architecture firms in the US, but really this is a typical conversation topic in gatherings with colleagues and friends. Would you say this is symptomatic of a larger issue in the architecture field?

Yeah! I think work-life balance is a fairly big issue for us. We are both the creative profession and a profession. We are creative people and professional people, and the kind of confluence of those two things really do mess in terms of our practice. If we’re an artist and we get up at 1PM, we might work until 3AM. But we would make our own way into where we would have the kind of meeting schedule, we have to work with consultants the way that we do.

So, the demands are, that we must make our practice do all the things a professional practice might do and then, on top of that, we have to act like an artist and do all the creative things an artist might do. So, in a way we’ve got two professions collided into one and I think that has a kind of effect whereby, the understanding of it is, if you only do the 9AM-5PM bit, you are not doing the artist bit. But if you’re doing the 5PM to midnight bit, you are managing to do both.

Honestly, COVID-19 has probably helped us readjust a little bit. I know that now, here I am on my little studio. I have two couches and I go over there between my meetings and I take a little nap, and no one has to know except you folks that have been privileged enough to be here today right now, that I do that. But people in my office know that I’ve always insisted that people take a time out at work. I installed lounge furniture as much for to nap on, as for everybody else to have a place to relax. In order for that lounge to be adopted by my staff we had to make mandatory attendance parties in the lounge space, and bring alcohol, so that people actually start to take up residence. It took about a year, and right before COVID-19, it was used daily by people, not only to take a break from work but also to have a different kind of relationship to the work that they’re doing; a much more casual, informal, or conversational relationship to the work. So, I think it’s true. It was an effort to break down the kind of monoculture, into something a little bit more manageable.

I love that it took one year to actually set the lounge area.

We had to make people use it as a party space.

…and then bribe them with alcohol, that always works.

Yeah!

Come to this place to relax! I like the nap between meetings in your studio, that’s perfect.

I only take one nap a day, but I do take a nap for 20 minutes, and it is usually after I eat lunch. Just so there is no false information out there.

We have to try that. So Regner and I—and I am sure other people as well—try to teach our students to develop their own voices as designers and to show us their particular way of seeing the world. Instead of imitating what others are doing, there’s immense value in finding out who they are. How they fit or don’t fit in the world, and in proposing new ways of imagining our spaces. Do you agree with this?

I am going to go back to my previous answer which is this that the profession of architecture is both a profession and a creative endeavor. There are two sides two to this profession. Not every single person that goes into architecture must fulfill that artistry side, yet every person that participates in architecture must understand that artist side. Therefore, I think people need to understand the creative impulses or what it is behind that creative impulse, and even if you are not one of those that are generating the new thinking, you must understand the new thinking. Everybody must have empathy. I think this about the world in general, but in particular in architecture.

Architecture it is an empathetic act, by designing a future-forward thing that is anticipating people’s behavior or is contributing people’s behavior. It is empathetic by its very nature, and so I think receiving training or encouragement to understand yourself is helping you to understand other people. In essence, what I am saying is, yes, I think that it’s essential in the training of an architect to get to know oneself—what make one tic—even if that’s not going to be the thing that you contribute to the field.

Not everybody has to think that if they do not have this unique voice, either from a design standpoint or from a personal history standpoint, that they are not going to be valued in the profession. I think the profession has a spot for everyone.

There are four partners in Diller Scofidio + Renfro. So, first, circulating back to the previous question, how would you say is your take on architecture, in dialogue or contrast with the others; and secondly, with the broad list of projects the firm has, does this then help decide which project would be led by whom?

I was brought into the firm in 1997, to mostly manage a project, that was the Brasserie53rd street in Manhattan. I was brought in as the kind of project manager. At that time, there were only four people: Liz, Rick, and two people that had work with them some time. But there wasn’t really a professional condition in the studio, and I had already had my own practice, and had built quite a few things with Smith-Miller + Hawkinson, my first office in New York. So I was brought in as sort of the adult in the room, which is bizarre. And so, I took the helm, sort of as the feet on the ground guy, but as soon we started doing design work together, Rick, Liz, and I bonded over the way we think about the world—as kind of outsiders, but inside-outsiders. She is a Jewish lady, he is a mixed race man, and I am a gay man, and so the three of us—and Ben had joined later, so I’m just going to talk of the foundation of the three—, we all have these kind of outside places.

I would say my queerness has influenced my positioning within the firm, and in fact the work that we take on a lot. I queered up the firm quite a bit, but it was already, actually, working on the margins in a kind of provocative place before I arrived. I think I simply slipped right into this notion of being a provocateur and became a full partner with Liz and Rick, as a design partner. Ben joined the firm a bit later than me, and we could tell right away, that like me, he was well-rounded; he could do everything. He could draw a building in CAD, he could conceptualize and speak about it, he could teach. So, we do each currently have a set of projects that we run. However, we make a point that all the partners contribute to all of the design projects when they start, and so, the projects are truly collaborative in nature. We don’t actually take a project and hoard it and not share it with another person in the firm, it’s very much shared.

Having said that, I think there’s gravitational pulls about which partner takes the kinds of projects they take, and my emphasis has drifted to a lot of academic work. I don’t consider myself anymore of an expert in academic work than my other partners, but I do think I have a lot of experience working with the various councils and boards, and approvals systems that are particular to universities and institutions. That’s certainly not the only work that I do, but that’s a large portion of my work in the firm right now.

Brasserie

Brasserie - Stars

What is the biggest difference between being a partner at a large firm, versus a small one? What was it like before for you? You previously mentioned that there are many business tasks to undertake and that you are lucky to be able to design about 3-5% of the time right now.

I can’t answer this question thoroughly because I’ve never been a partner anywhere else, except in my own firm, which I did co-found with a classmate of mine from Rice University. From what I see collaborating with large firms, which we do all the time, the scale of the projects tend to be larger in bigger firms. For instance, we’ve never done a big project like—I’m going to use a bad example— Hudson Yards. KPF did an enormous contribution, two towers and the base. It’s something we wouldn’t do, it’s not in our category of interest. Not saying that these projects shouldn’t happen or aren’t important to city-making, it’s just that we don’t do them. I expect that that is one of the big differences. We also don’t do infrastructure projects, although I would love to design an airport, it’s one of my fantasies, but we’ve not done such a thing yet. Although it seems like we are entertaining the idea of doing a European train station. Our practice is starting to resemble a large-scale architecture office, but we do run it slightly differently, as all the partners participate, in the design which I know does not happen in larger scale firms.

Who knows, maybe one day you’ll get to design an airport.

Oh wonderful! This is a funny thing, when I was a kid, I used to design airlines because I had a fascination with air travel. I made this airline called ENDICO, and it was based in San Juan. I don’t have any of this because my brother burned all my collateral material, but I designed the logo, I designed the route map, I designed the uniforms for the flight attendants. I imagined it was based in San Juan, I’ve never been to San Juan I had no idea what Puerto Rico was. However I knew it was exotic sounding, and that I would own this massive worldwide airline based in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

The Shed - Steel Structure (Photo by Iwan Baan)

The Shed - Steel Structure (Photo by Iwan Baan)

The Shed - Bogie System (Photo by Iwan Baan)

The Shed - Interior (Photo by Iwan Baan)

The Shed (Photo by Iwan Baan)

The Shed - Photography by TimothySchenck

There is this popular meme about how upon graduating from architecture school, architects are hired to do bathrooms and restrooms. There’s this notion of restrooms as being dull or afterthoughts. But in your projects, restrooms feel like a complete experience and a prominent part of the design, including everything from the space to the last details such as the signage, which are customized with text such as “we support gender diversity”. What can you tell me about your view of architecture and its roles in social issues of gender equality and general inclusivity?

I am a real believer that every design project is as important and meaningful as any other design project. If you look at our website, you will find that our practice ranges from the design of a drinking glass to master plans of entire islands off of China. Every design problem could generate as much interest as any other design problem, especially in places like restrooms where you are so intimate with your own body. It’s a place where gender is called into question. So much in the history of queerness has happened in bathrooms that is hard not to think of bathrooms as a wonderful design problem.

Frankly, we did not write that text in the MoMa bathroom sign, MoMa did. We were designing MoMa during the time when the laws were changing, and we wanted to be completely supportive of new ways of thinking about gender and in the middle of design process we changed our binary bathrooms. We had to keep them binary because enough people needed to see binary, but we redesigned them so that each stall would be completely independent and concealed. We had to change our mechanical system in order to support that. We essentially took the main doors off the bathrooms and made these wonderful peek-a-boo mirrors that float and let people take glimpses of other people’s bodies.

The bathroom has been a place that we have investigated a lot. The Brasserie, which I ended up co-designing with Liz and Rick—the project that brought me to what was then Diller Scofidio—, the bathrooms was one of the most important features in that restaurant. Unfortunately, it has been demolished now, but it was all about accidental glances, voyeurism, and confusion of the sexes. The mirror sinks and the bathroom stalls were all held with one wall that split the men from the women. This was done 21 years ago, so the gender issues were not front and center, but we were already interrogating that division and calling into question that necessity to strike differences between male and female, and blurring the line as much as we could so that people would feel comfortable with the space being shared and the structure of each side being one in the same.

MoMA Renovation and Expansion (Photo by Iwan Baan)

MoMA Renovation and Expansion (Photo by Iwan Baan)

You mentioned that part of your knowledge was acquired by building something from start to finish with your own hands. How does the experience of making translate to structural innovative projects such as the Shed—with its massive wheels for space transformation—or the MoMa—where the stairs’ landings and the entrance canopy are almost paper thin?

It goes back to the question about knowing yourself and getting to know yourself as a being in the world. Knowing how to make something is embedding that knowledge into your being. The first time you ‘drywall’ a saw up into the ceiling and, not know where it is when you are looking for it, realized you left the saw in the ceiling; or when you electrocute yourself when you’re doing the wiring to your kitchen; you made all the kitchen cabinets on your own and had to know how to do the measurements of a toe kick, and how high to make a cabinet. When all of those things are learned inherently, even at that small scale, then you are so much better equipped to make informed decisions at a large scale.

The reason that even doing a bathroom renovation by yourself is such a translatable and scalable activity is because we’re still all human bodies. So far, I don’t know anybody who’s become an A.I., but I know that they are trying. We’re all different shapes and sizes, and some are completely able-bodied while others are not. We’re all different, but we still have a body, we still have a size, we still have various things that are pretty much the same from body to body. So, you can translate those things to the height of a toe-kick or how to position a toilet in a room. Those things translate to on how to make a door in an urban environment. Where are people coming from? How are they moving through the city? What are they going to see and when are they going to see it?

Then, onto more daring structures like the Shed, which is knowing some real basics of physics and movement, I think it is really translatable and scalable. Of course, it helps when you work with great engineers that help you figure out your crazy projects. For example, we worked with Thornton Tomasetti, that has a kinetics division. This was right up their alley. I do want to mention that architecture is not a sole effort, going back to the comment about knowing yourself whether you’re the creative side of the business or the “getting it done” side, they are all intertwined, and it depends on collaboration with people including people in your own office, my partners, people outside of the office, my clients. Every conversation I have with my clients is a collaboration. I’m getting feedback and what the program needs from them and that is being translated to me and my team into some physical form. Sometimes, not always as a physical form, because we do work in theater, dance, and live performances too. So, that was a rambling way of talking about building from a personal scale and how that translates to what is possible at a very large scale.

I like how you included the engineers. Seeing these projects, I bet that before they inaugurated them engineers couldn’t even sleep. They are very innovative.

I think they still can’t sleep. It is innovative. There were a lot of firsts, and first always means there are going to be some failures, that’s just the way it works. If you do something that’s a first, you risk failure, and everyone is on board and understands that something may not work right. But with that, you are going to be able to do things that no one else has done ever in the history of the world; that’s the trade-off.

Columbia Business School (Photo by Timothy Schenck)

Columbia Business School (Photo by timothuy Schenck)

What are some of your larger concerns in architecture? What do you think we need to think more of? How do we get there?

Yes, I think that’s the question on everyone’s mind. I think there is one obvious problem in the world, but there is not an obvious solution. And the problem is inequity. It’s particularly true of New York, and I assume most of you have been here and understand that the city has grown unaffordable for most people—most but the wealthiest—and it is certainly not a place that our COVID first responders can afford to live in, and hardly be in. I think that it’s such hypocrisy and shame, and COVID has unearthed not just that with first responders and the expenses of the city, but also has unearthed in this country, in the United States of America.

The history of slavery and racism is completely embedded through and throughout our country. These are the problems that I feel like we need to address. But I don’t exactly know how we do that as architects. One thing we are trying to do in our studio is to engage in more social projects. So, low-income housing, we are trying to work with some innovative developers whose work is focused only on housing to try to come up with new models in the States. Ownership, the traditional way of gaining wealth in this country is through ownership of property. Thinking at the level of policy, how can architecture and policy help to overcome the issue of wealth acquisition to everyone in this country? Education is a huge issue in this country and across the world. Those are things that have to be addressed and architecture can be a tool to help that. But, in order to really get in and address the world’s problems, we probably have to dig deeper and get into issues of zoning, code, policy, and city planning. Things that really, before architects enter the stage, are determined.

In terms of urban mobility, what do you think of other cities taking or following what the High Line has become or done as a catalyzer in the city, such as, some proposing an elevating sidewalk or sky guarded? What is your opinion on the relationship of the pedestrians with the ground level?

I am going to twist the question into something more tricky. The High Line has been incredibly successful and copied around the world. It’s not unique meaning it’s not the only rails to trails project that there is. That’s something that has been happening for some time. But it is probably the most identifiable because of its elevated status, literally elevated in two ways. It got a lot of funding from the private world and some from the city, of course, but also it is elevated above the streets in New York, putting pedestrians in this privileged place. But I am going to add on a sort of problematic issue, which I think the question is hinting at, which is, what do I think about these projects that are coming through all these cities, that are transforming their spaces and in so doing, gentrifying their spaces, raising the property values, and in effect, making those cities not affordable or usable for the residents that probably helped hype or where in those neighborhoods before the gentrification happened?

This is something that has plagued the High Line and has been plaguing in other developments in New York City and other cities, and I think we’re trying very hard to think differently when we start projects like the High Line. How to safeguard against the trickledown economic impacts that are pejorative or negative for the local residents. There is no part of this that is exactly like the High Line, you know, this completely elevated rail. I think I was getting in one of the earlier discussion questions, every project starts with its own set of inputs and each project is different than the other, even when though they might have some similarities, you know, they are going to respond to their sites in a different way. And I think what we need to do is make sure, as best as we can, that our projects respond to not just a physical condition, like an elevated condition or on the ground, but a set of other conditions that are often impossible to see. They require quite a bit of research or knowledge of the place, and that includes the local indigenous or the local resident population—what this project does, both to elevate and to oppress or suppress or harm that population. So, these are harder things to quantify, but they are really important.

High Line - Photography by Timothy Schenck

High Line - Photography by Timothy Schenck

What else from your childhood do you think you are carrying into your practice, design, research, etc., and into your architectural life?

That’s a good question. You know, I was a clarinet player, starting in the 6th grade. In a way, playing clarinet was a way for me to make an excuse of why I wasn’t out trying to play, to be ‘one of the boys’—because I wasn’t. And it also gave me something to focus on and excel at. I was very, very good. I got a scholarship into Rice, where I later studied architecture, fully paid in the Shepherd School of Music playing clarinet. But I think one of the things that happened with that is, I kind of… a sense of performance and also engagement with the performing arts, and so the sense of performances is partly like what I am doing right here with you, which is simply, I love having a conversation. I don’t mind being on stage, I rarely get stage fright. It’s fun to have a dynamic with an audience, being on stage. I think I learned that in my childhood. I was precautious, but I was also incredibly fearful, and I am still, you know, about most things, partly because of my sexuality. I think I became hypersensitive to everything that’s happening around me. And I believe that that sensitivity has also translated to a sense of empathy in the way that I design and work with people.

How do you, having different perspectives and inspirations in other methodologies, help you construct your personal vision of architecture?

I am wondering if by other methodologies you mean like dance, working in arts and various things like that. Is that right? Is that the way we are going to interpret that?

Yes, other disciplines.

Other disciplines. Yes. You know, I think in all the work that we do, we are trying to uncover something is hidden. And it could be hidden in the way that we behave or the way that we walk through a city or the way that we assess something in a performance or have you… We focus a lot on vision, the idea of seeing. How do you see? What is visuality? A lot of the work in our early artwork had to do with tricking the vision, like making you see things that you know are impossible, such as putting a 45-degree mirror over a stage or in the Blur Building, making a whiteout condition, as a piece of architecture that denies your vision. Those explorations of vision, notions of seeing, of hindrance, excitement, or amplification of vision are things that have found their way into our buildings a lot. The ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts) portals, that frames the water. In number of other projects, almost every project we have done, we play, with notions of visions, foregrounds and space of deep space, confusions of what you are seeing so are tricking, we are now very interested in that, quite a bit. So, they do reinforce one another, but they are also working toward the same end, which is a heightened way of experiencing things, in a kind of new way we experience seeing things.

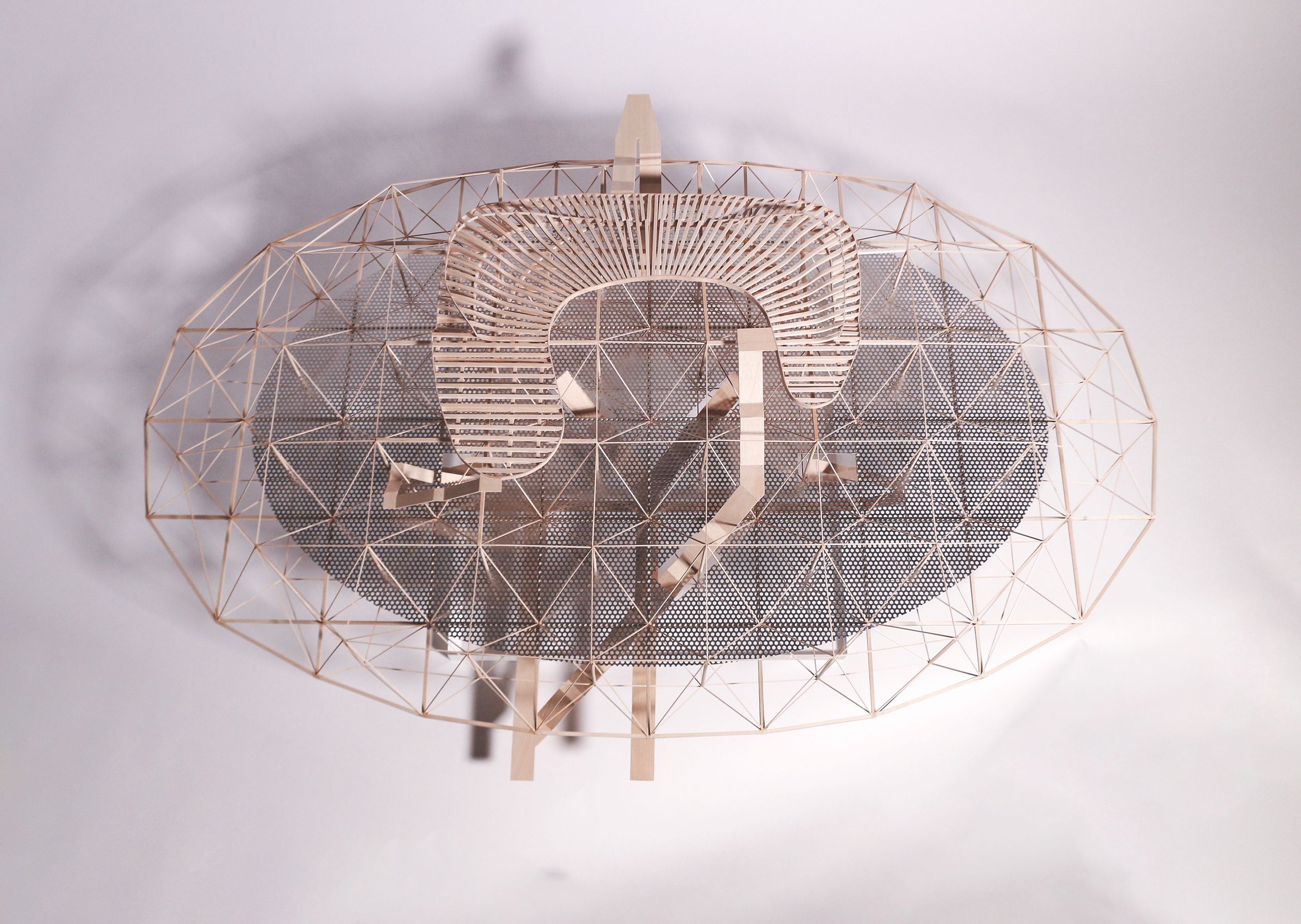

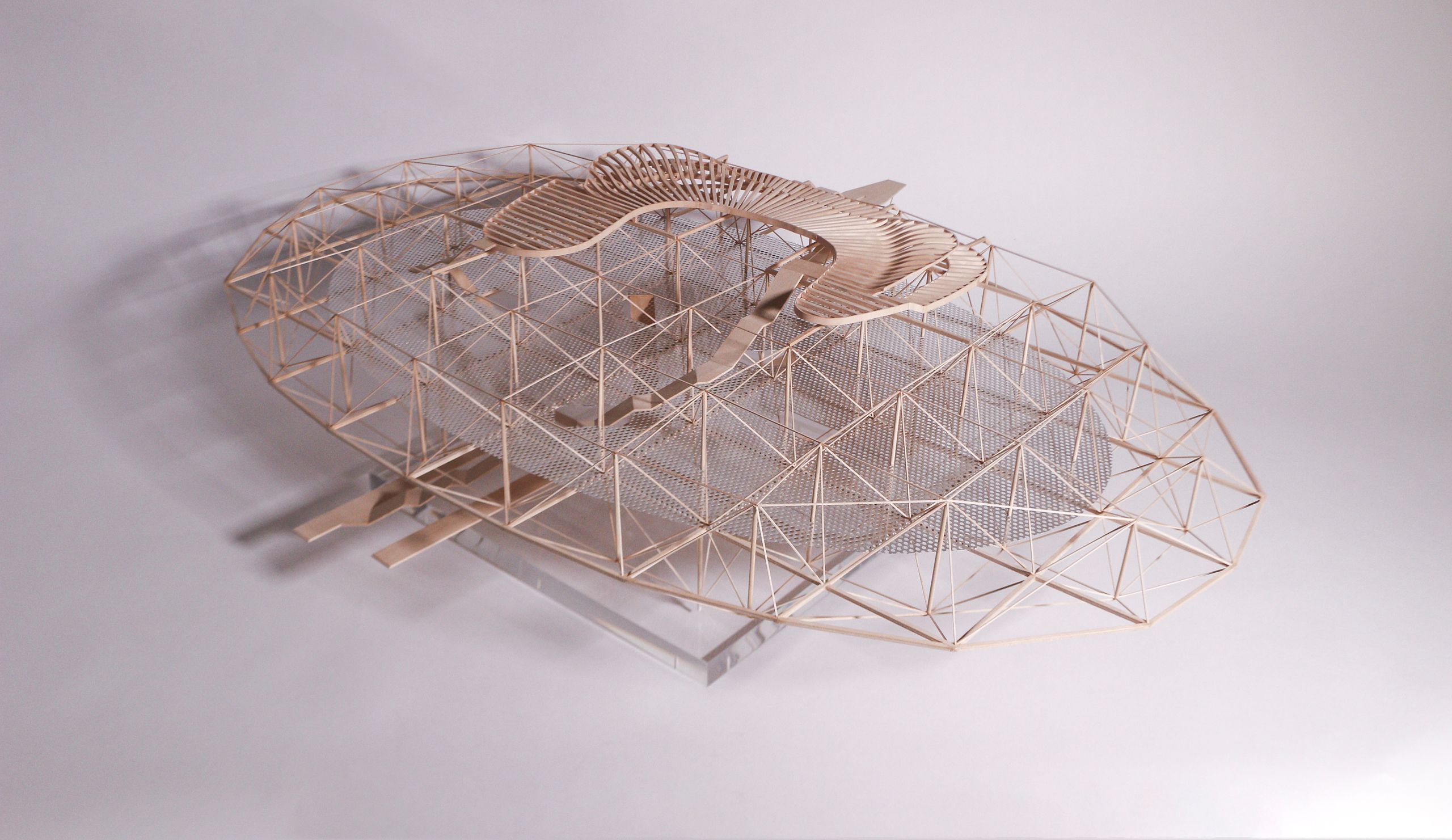

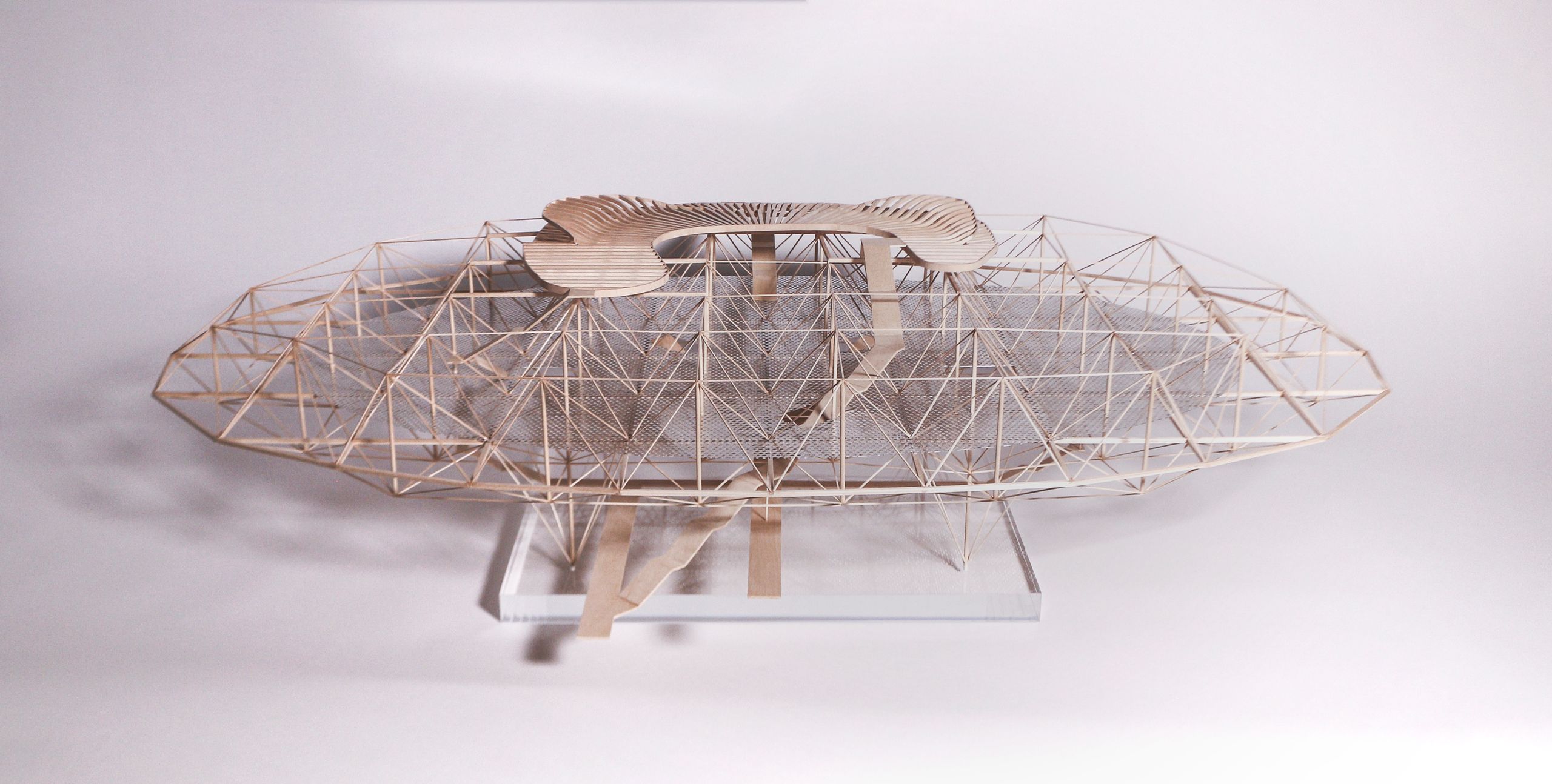

Blur Building - Exiting Site

Blur Bluiding Physical Model

Blur Bluiding Physical Model

Blur Bluiding Physical Model

This is a follow up to your question of equity. Do you feel that the High Line can address the effects that it had on inequity with the surrounding area?

I think the High Line was an object lesson at this point, and I think in order to have safeguarded against it, and to have dealt with inequity as an issue, we would have done things slightly differently in the very beginning. We would have worked with the city to safeguard local businesses from being forced out of their places because of rising rents. We would have set up coalitions with local residents—which we are doing now—and I think we are readdressing some of the problems that local residents are getting training for. Horticulture training, management, building maintenance, you know, a whole bunch of things that the park can offer. We are doing education programs, of course, there is a lot of arts going on the High Line. I think we are kind of coming back and readdressing it, but if we had known what we know now, we would have started the project differently. We are now advising our clients when we are getting into rejuvenation projects that are urban in nature, to think deeply ahead of time. So, as to say part against sort of built-in inequities.

High Line - Photography by Iwan Baan

What do you think about the living pod trend that’s being pushed recently randomly over social media, as properties and rent become more and more unaffordable for the majority of the newer generations? And also, thank you for this wonderful talk.

Thank you for the question. You know, I haven’t been paying total attention to the pod movement. I think that what we have to ask is, are all human needs being satisfied with that living condition? And, if they are not, I believe we should all endeavor to maybe establish a universal living condition that, which I think will include fresh air, daylight, and some form of outdoor connection. I don’t know, I mean, I am sure there are international standards that are out there. You know, to me, because I don’t know too much about the pods, it sounds horrible and it sounds like an admission that in this world we are forced to have a completely bifurcated world of people who have money and people who do not. And I think that that is something we need to all be working against.

What advice would you give to graduate students in terms of future opportunities in architecture and design?

Oh! Go find a Job! Well, I will hit your wagon to a place that’s doing good work. Meaning, not doing beautiful work, not doing fancy work necessarily, but doing meaningful work. I think that’s what you need to do for yourself and for the planet.

Thank you so much Charles and to your whole team for helping us set this up. We are super excited to have you and it’s great that you’ll be part of the upcoming issue. You’ll receive our care package maybe next week if the USPS does not let us down.

Oh boy! It was wonderful to chat with you, I liked your questions a lot, I love your background paper and let’s all be in touch!

SHELLAR GARCÍA

Architect and Instructor

Universidad de Puerto Rico (San Juan, PR)

Shellar García is a licensed architect and educator. She holds a Bachelor in Environmental Design from the University of Puerto Rico and a Master in Architecture from California College of the Arts, in San Francisco. At the University of Puerto Rico School of Architecture, she teaches fourth year design and drawing. In her eponymous San Juan-based practice, Garcia’s work directs a functional design towards craftsmanship and details. Previously, García has worked at Coleman Davis Pagán Arquitetos and CMA Architects & Engineers, LLC. Her research interests are currently focused on the inclusivity of the deaf community and how architecture can perform a beneficial role.